In a couple of my previous posts, I’ve stressed my amazement with the quick change in attitude among Helsinki’s urban planners. The message from the planning authorities is that they have chosen to increasingly question the conventional modernist planning ideology and are now actively seeking to add elements of a more urbanist approach to Helsinki’s upcoming steering document, the new city plan.

Now that the first excitement is slowly beginning to settle down, it’s time to start thinking ahead. And what I’ve been thinking about this time touches upon the management of links between planning ideologies and planning practice. Namely, I would like to see one classic planning debate enter the Helsinki discussions, because A) it has not been discussed at all in this process; and B) it plays a significant role in the on-the-ground implementation of the new city plan.

Let me elaborate. In its new draft plan, Helsinki is chiefly calling for the development of specific urban characters in select locales: “The downtown core will be expanded by increasing the effectiveness of land use in motorway environments and by transforming them into urban city space” and furthermore, “new construction is mainly located around the suburban railway stations. The suburbs have become centres of urban living, services and workplaces”. Ultimately, the aim is to “bring the city back to the city”. These ideas are coupled with visualizations that leave little room for interpretation on the nature of the desired end product.

For my studies last year, thesis research and current work project I’ve had the opportunity to look at some of the newest master plans and development strategies European metropolitan cities are putting forward. An often recurring theme I’ve come across is what we are now witnessing in Helsinki: the elevation of design as a guiding planning principle. Some talk about urban design, some about urban form and others about places, but the bottom line in simple terms is that more powerfully than during the past decades, the steering documents describe parameters of the intended real-life neighborhoods and urban development projects.

Across Europe, in North America, as well as here in Finland, one of the key reasons why cities are getting ecstatic about urban form is the poor performance of the conventional modernist zoning approach to this end – something we can see and experience in our monotonous everyday urban landscapes.

For instance, Stockholm’s plan “The Walkable City” from 2010 calls to heal “the wounds that have been left in the fabric of the city… with the advent of Modernism. […] In the future, the walkable city will not stop at the historic tollgates around the centre, but will stretch far beyond and link up the whole of Stockholm.” The Amsterdam 2040 Structural Vision more elaborately states that the “quality of life in the city is becoming increasingly important, and along with this the layout and the use of the public domain” and thereby “Amsterdam’s streets, squares and waterside embankments must therefore meet high design standards in their layout”.

Yet the problem I want to discuss is that it is not as easy as snapping your fingers and sketching a few visualizations of desired neighborhoods to make such places happen. While it’s already difficult to just shake off stubborn ideas, we need to keep clear in mind that planning ideologies also have an institutional fix.

In Finland, our entire planning system currently effectively serves the conventional modernism-inspired and use-based practice of planning. Therefore, the system deep down is largely at odds with the actual realization of the Helsinki planners’ urban daydreams. Just as the urban environments our competing planning ideologies cherish, the practice of conventional use-based planning and place/form-based planning are in strict contrast.

My concern and question is will Helsinki’s enthusiasm to plan design first also have an institutional dimension to back it up or will the desired urban outcomes just stay as advisory elements to be repeated in celebratory speeches?

Elsewhere, planning practice has often needed to evolve one way or another while elevating design in the center of planning – or “form and pattern over use”, as Emily Talen (2013) puts it. With respect to the outcome, in some cases this is done via the subtle use of urban imaginary new development must follow, while other cities have gone further to introduce mandatory design controls to make sure the city gets what it wants.

Talen lists examples of North American design-led planning concepts such as “traditional neighbourhood development ordinances, mixed-use and live/work codes, transit-oriented development ordinances, transit area codes, transect-based codes, smart-growth codes, sustainable codes, transit-supportive codes, urbanist codes, and green-building codes of various stripes” which have all emerged to regulate the built environment as means to deliver desired places instead of non-places.

Patsy Healey (1999) adds that place/design-focused planning is often also affiliated with a desire to move away from the traditional format of using land-use zones because the practice is experienced to be “place-blind”. The reason is that the conventional one-size-fits-all approach to planning understands best the singular and ‘hard’ language of quantitative data, but not the plural and fluid ‘soft’ concepts of place, locality and constructions of place identities. A cozy street is an experience, not easily understood by Excel.

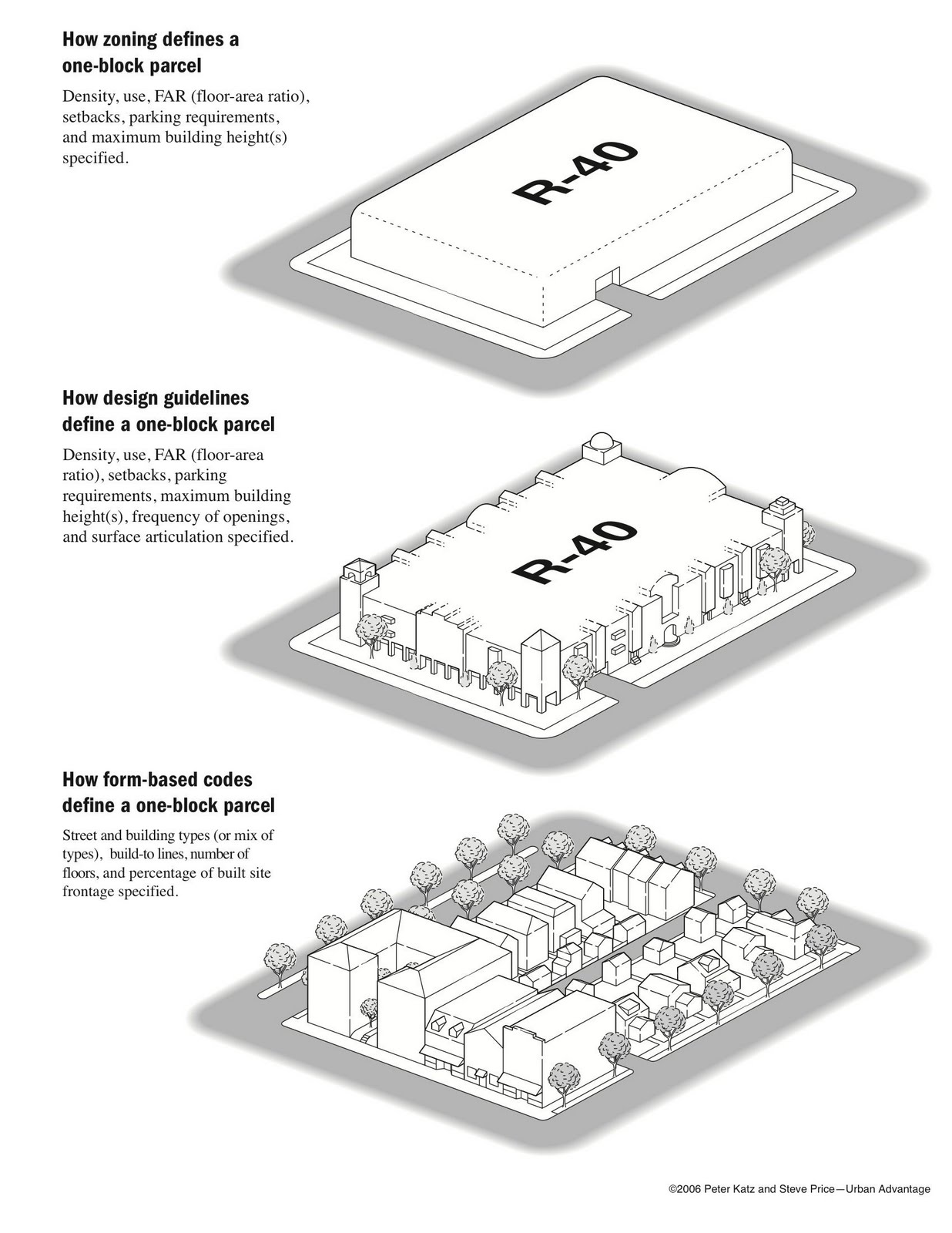

The fundamental difference between the form/place-based and use-based approaches to planning is that the latter primarily understands the city as a two-dimensional map composed of zones of non-compatible uses instead of a three-dimensional complex unit which comprises of different character areas and development patterns.

Moreover, the use-based planning approach is founded upon on a “culture of separation” – as Talen expresses it – which defines the way planning practice is organized. That is, setting for example “residential areas”, “commercial areas” and “office areas” apart from each other, much like in the classic computer game SimCity for those of you who remember. The different elements or codes that passively determine the development of these vague areas into real urban space are governed in separate bureaus and departments which each specialize in excelling in their niche over the whole. Shout “mixed-use” and you will give gray hair to a lot of people in this system.

In the place-based planning thought, the end product conversely becomes a horizontal planning issue that presupposes close-knit collaboration between different types of planning expertize. The whole is greater than the sum of its parts in this business. Furthermore, instead of controlling the distribution of specific uses, emphasis is placed on regulating buildings and public space. The idea is to actively support different kinds of neighborhoods to embrace the plurality of cities.

Probably the furthest taken example to this end is the New Urbanist-driven practice of Form-Based Codes gaining ground in North America. They have captured the philosophy of place-based planning in their Transect tool, which intends to replace use-based development zones by a continuum of urban environments to act as a roadmap for new development. The tool divides the city into character zones of different intensities and their own “DNA” for quality that future development needs to comply with.

The point I want to make is that to proceed down the road of elevating design/places/urban form as a key planning principle, supplementary changes within the structures of planning are inevitable to get something done effectively. If I may suggest, a good direction for Helsinki to seek guidance from is the city of Antwerp in Belgium. It is an excellent European real-life case of a city that has decided to go design first; the winner of the 2013 “European City of the Year” title awarded by the Academy of Urbanism.

With the adoption of its strategic spatial structure plan in 2006, Antwerp as a community chose seven images that combine the existing different faces of the city as well as future directions. These imageries now respectively guide new development interventions. In addition, the city reshuffled its planning organization to capitalize on the idea of putting “spatial quality on center stage” and to approach it “from different societal perspectives so as to maintain an integral concept of quality.” Finally, I also salute the idea of installing an independent quality supervisor (Stadsbouwmeester) to oversee that new development actually resonates with what’s intended.

In Helsinki, it’s a very welcome move that great places have begun to matter more and more in the minds of planners. But for the time being, going that extra mile to uncover and assess the connections between planning practice and its on-the-ground effects is still a matter paid far too little attention to for those dreams to come true.

References:

Healey, Patsy (1999). Institutionalist Analysis, Communicative Planning, and Shaping Places. Journal of Planning Education and Research 19, 111-21.

Talen, Emily (2013). Zoning For and Against Sprawl: The Case for Form-Based Codes. Journal of Urban Design 18:2, 175-200.

Leave a Reply to Prof., Univ. of OklahomaCancel reply